They made a tremendous fuss / about everything, these Reformers […] / And as they proceed with their investigation, / they find an endless number of useless things to eliminate […] / And when, all being well, they finish the job, / it will be a miracle if anything’s left at all.

These lines from revered 20th-century Greek poet, C.P. Cavafy, were written, not five years ago as the Troika arrived in Greece demanding the large-scale sell-off of state assets, but in 1928 amid the economic turmoil of the 1920s and 30s. Crisis has always brought the wolves to the gates. In modern Greece, these wolves have been not only the European Commission, European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and speculators, but also cultural institutions and other creative professionals. The last five years have seen Rethink Athens, unMonastery, IdeasCity Athens, as well as Documenta and Reactivate Athens – all projects where, to varying degrees, external actors have sought to generate strategies for how to solve or best represent the city’s problems. “A part of the artistic world tends to run to wherever they can locate pain and woe,” Yorgos Tzirtzilakis, consultant at the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Arte, recently commented on the sudden surge of interest in Greece.

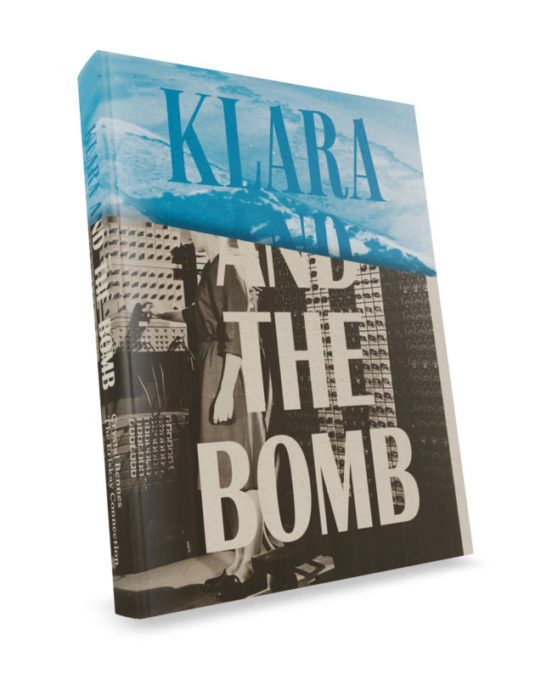

Reactivate Athens was a project which took place in a vacant shopfront in central Athens between late November 2013 and March 2014. It originated with Urban-Think Tank (U-TT) founder Alfredo Brillembourg, who then partnered with the Onassis Foundation to realise the project – to create 101 ideas which could then be deployed, not only in Athens, but in other crisis-struck cities across the globe. The results of their project are collected in a 464-page book, a quarter of which is dedicated to introductory essays; the rest, photographs of Athens and the presentation of the 101 ideas. On the back cover of Reactivate Athens, Design Museum curator and sometime U-TT collaborator Justin McGuirk praises the project: “not letting the crisis goes to waste, this book finds Athens to be fertile ground.” In a 2016 interview with Damn magazine, U-TT founder Alfredo Brillembourg explains the appeal of Athens in his own words: “We decided to do a project in Europe and […] Athens was by far the most interesting city, as of course it was already in crisis.” Whether intentionally or not, before the spine has been creased, Reactivate Athens sets itself up as a project which seeks to benefit from the crisis of others.

Bottom-up urban and social strategies for dealing with the fallout of the crisis in Athens have interested me since 2014. Three years is not a long time and, prior to this sudden interest, I never had any meaningful engagement with the city. In the summer of 2015, I spent a week in Athens researching a piece on the subject.[1] I met with Athenians, newcomers, even visitors, to talk about how to live when many government services were eroding, even failing altogether, all at a time when media attention alternated between intense coverage and total absence of interest. I met activists working to ensure that state utilities didn’t become illegally privatised; co-op-run grocers helping to keep rural famers in business; unemployed Greeks organising soup kitchens on the street to keep people fed; even groups publishing lists of current initiatives to give the press something else to write about when many stories placed blame on the shoulders of supposedly lazy, irresponsible Greeks. In some ways, I too was a wolf, although I sought to be a responsible one.

While Reactivate Athens took place in late-2013 and early 2014, it’s interesting that the book is being published in 2017. Perhaps it’s simply the case that, as with many publishing projects, delays are inevitable. Whatever the case, the effect is that publication has coincided with Documenta, one of the largest contemporary art events in the world. Typically held every five years in Kassel, for the first time since its founding in 1955, the 2017 edition is also taking place in Athens. Since opening in April, Documenta has been widely criticised in the art press as a parasitic event with neo-colonial overtones; German cultural imperialism taking advantage of interest in crisis-struck Athens for its own benefit. “Once the European troika has finished plundering infrastructure and resources in Greece, crisis-as-capital will perhaps be the only remaining ‘resource’ from an outside perspective,” suggested writer and curator Iliana Fokianaki in Apollo. “Of course, Greeks don’t see much return for this value.”

In the book, Brillembourg and Klumpner’s introductory essay – ‘Athens is Burning’ – sets out their vision for engaging with Athens. Does a city in crisis produce a certain kind of knowledge, they ask? “Against a backdrop of prolonged unrest and uncertainty, how can the public participate in processes of urban and social change?” Two interesting questions. However, rather than expand, the pair set out on a dérive, taking in the city’s “unmistakable decline” while attempting to identify its hidden potential. They start at the main railway station and imagine it transformed; better integrated into its surrounding area, but also “a place to which people will be drawn from near and far just for the shared experience.”

Their next stop is an abandoned lot near Omonia Square, an area which “appears to be in decline […] [an] overt presence of drug use and prostitution enhances these perceptions.” This is confusingly following by mention of the square’s role as a commercial hub and its cultural reinvigoration thanks to the close proximity of the renovated National Theatre. However, no sense is given of the historical and cultural context of Omonia – no indication that this square has symbolic importance for the city (among other things, Omonia is the true centre of the city, the point from which all distances between Athens and other Greek cities is measured). In their vacant lot, the pair propose an outdoor theatre and cinema as an acupunctural project to provide “a high-value, catalytic public space for the city.” It’s not necessarily a bad idea, but in a city that already has a rich and long-standing tradition of open-air cinemas in roof gardens, car parks and parks, why present the idea as totally disconnected from this tradition? When a dérive is a walk taken by two men with little apparent knowledge or understanding of the context of the spaces and places they’re re-imagining, it becomes a superficial, almost purely aesthetic act, rather than a process of meaningful political engagement.

Brillembourg and Klumpner present Reactivate Athens as bringing “fresh models of thought and practice [to Athens] […] and a radical reorientation of thinking” and the book as a project “to ensure that a humane new expression of civic space prevails in Athens.” The choice of words such as “fresh” and “new”, not to mention the prefix “re” in “reorientation”, but crucially, “reactivate” are problematic; a writing-over of the voices of people and communities who live and work here presented as a platform for “strengthened civic agency.” Reactivate Athens announced that it collected 3,472 ideas from Athenians through online surveys, but in the introductory essay, there’s little trace of their voices, except as anonymous victims – of urban decline, drug use and prostitution, even their rather than public-transportation users. Have we forgotten that the language of decay and decline is often the first stage of justification in profit-driven gentrification? There’s little appreciation of the fact that Athenians not only have their own agency, but that they have long been exercising it in ingenious, productive ways.

Remarkably, somewhere between December 2013 and the publication of this book, Brillembourg’s view of Athens underwent a meteorological, metaphorical shift. At the project’s launch event in December 2013, Brillembourg introduced Reactivate Athens thus: “Athens is a city living in a long winter […] which has frozen all the potential of this city.” Unsurprisingly, such comments were coolly received by many. Writing in January 2014 on Koino Athina, a blog about urban actions in Athens, architect Eleni Tzirtzilaki called out Alfredo’s description of the city as the result of a lack of interest in “learning [about] the present oases created by city-dwellers who work, often unpaid, because they love their city and recognise and fight for its potential.” She continues, claiming that the problem lies not with Athenians, those “who have imagined another city which we are now seeking to create,” but with obstacles on a policy or planning level, “those who believe that a city should be constructed top-down”. Tzirtzilaki positions Brillembourg not as facilitator, but as part of this machine of top-down planning – “an architect of globalization who views Caracas, Amman, Cape Town [all the same].”

Similarly, Maris Kalantidis, a Berlin-based Athenian city planner, and Maria Papadimitriou, an artist and professor at the Architecture School of the University of Thessaly, who both participated in Reactivate Athens, wrote a measured, yet critical February 2014 op-ed in the main left-wing paper, Avgi, echoing Tzirtzilaki. In a different context, Reactivate Athens would be less fraught, they wrote, but given the constant weakening of institutional power a project like this (which felt, they said, at times like a campaign exercise for mayor Giorgos Kaminis) must be extremely well-balanced. The pair repeated Tzirtzilaki’s comments that “neither ideas nor designs for Athens are lacking, nor an interest in the city’s future.” Rather, they wrote, what’s missing are “appropriate institutions to implement” ideas, but above all, “the political will for implementation.” Kalantidis and Papadimitriou also expressed reservations at the project’s presentation, particularly “the casualness with which ideas are expressed about Athens, as well as the systematic indifference to the knowledge or suggestions which have been and continue to be produced by serious scholars on the ground.”

Others, however, welcomed U-TT and Reactivate Athens, seeing the project as a way to connect the many, fragmented strands of individual actions in the city through Brillembourg’s charismatic leadership. One of the trio of initiators of Traces of Commerce, a project to bring city-centre commercial arcades back into use, in January 2014 Martha Giannakopoulou wrote approvingly that the project marked, “the first time that a participatory planning process had been carried out on this scale in Greece.”

In the four essays following Brillembourg and Klumpner’s introductory stroll, U-TT staffers Alexis Kalagas and Katerina Kourkoula look at Athens through the lens of previous crises in 1923 and the period following World War 2 to argue that the strengthening of collective, rather than purely individual, agency is needed in a city where past crises encouraged a sense of ownership of private rather than public spaces. But even Kalagas and Kourkoula present Athenians as lacking in their inability to channel their “energy and imagination into a new spatial approach.” Thomas Maloutas, Professor of Human Geography at Harokopio University in Athens, provides an overview of social relations and the competing interests which are acting to re-shape the city centre, looking at the flight of mostly affluent Athenians from the city centre beginning in the 1970s and subsequent displacement of state agencies to the periphery. In ‘Policy and Governance Tools for Change’, architect Maria Kaltsa calls on the government to formulate innovative policies and strategies, targeted incentives, and a new regulatory landscape to support social economies. Kaltsa outlines one of Reactivate Athens’ more meaningful ideas, developed in collaboration with a team from the University of Thessaly, in which the City of Athens would use EU funds to rent vacant apartments as social housing. In exchange, tenants would be required, for example, to assist elderly individuals living in the same building or nearby.

As for the 101 ideas, only 50 are fleshed out in any detail. These 50, separated into categories of housing and vacancy, economy, immigration, health and safety, mobility, poverty and vulnerability, and culture and identity are each accompanied by a photograph, a drawing and around 150 words of text. Ideas 51–101 are allocated one sentence each in five pages at the back of the book. Fascinatingly, the 400 ideas collected from members of the public as part of the Reactivate Athens surveys are listed in an appendix. Comparing the differences between the U-TT ideas – for example, idea 4, plug in – plug on, a kit of parts to allow temporary use of unfinished buildings; idea 30, vertical gym (deployed previously by U-TT in Chacao, Caracas); idea 48, crowdsourced city, an already-defunct app designed to open-source map and log ideas for the reactivation of the city centre – and the ideas submitted by the public is revealing. Unsurprisingly, the public display more interest in economic incentives to bring businesses and residential use back to the city centre, garbage collection, lighting, improved parking provisions and extended metro hours.

What pointedly stands out is the lack of connection between proposed ideas and pre-existing initiatives. Of the 50 proposals, only seven are credited as “seen in Athens”, even though a number of the ideas – such as mobile social kitchen and social occupancy – have numerous extant examples in the city. There’s Oallos Anthropos, for example, a group of unemployed Greeks who operate a mobile soup kitchen in the city centre; or Options FoodLab, a kitchen and food-training space founded to connect locals, immigrants and refugees. There’s City Plaza Hotel, the latest in a long line of Athenian refugee housing projects, which opened last year in a hotel which had been empty for seven years a few blocks from the main railway station and operates entirely without NGO or government support. For almost every one of the first 50 proposals, I could list at least one similar project in Athens.

This isn’t to say that one can’t and shouldn’t learn from what’s happening elsewhere and deploy similar strategies in Athens or other crisis-hit cities. But why not adopt a position of learning from Athens, rather than imposing on it from outside, insisting that its individual initiatives are ineffectual and that public-policy change must be the ultimate goal. The latter point seems particularly ill-considered in a city where local and state-level policies are often demonstrably hostile to its citizens’ concerns.

Since their early days in Caracas, U-TT have built a reputation for important work, drawing attention to slum conditions in Venezuela and elsewhere. But their work in Caracas is different to this project in Athens, and perhaps the Documenta parallel is telling. When you successfully build something – an art festival or a model of working – people take notice. Sometimes people ask you to bring your model elsewhere and sometimes you decide of your own volition to take that model elsewhere. But Athens is not the same as the slums of Caracas. And although Reactivate Athens makes the point that its 101 ideas are not exclusively context-specific and could, by extension be applied to cities all over the world, the people who live in the city whose name is on this book’s cover are specific to their context. If U-TT want to publish context-free ideas which could be deployed in slums or crisis-struck cities across the world, then do that. But, if they derive their ideas from or link their ideas to a specific place, they have a responsibility to that place and to people who live there. And that requires much more care than mere survey collection.

This article was originally published in Disegno #15. Support print