The city too has learned.

She knows

how to shed some bricks without breaking.

We Who Have Decided to Live in Autumn,

Zeina Hashem Beck, 2013

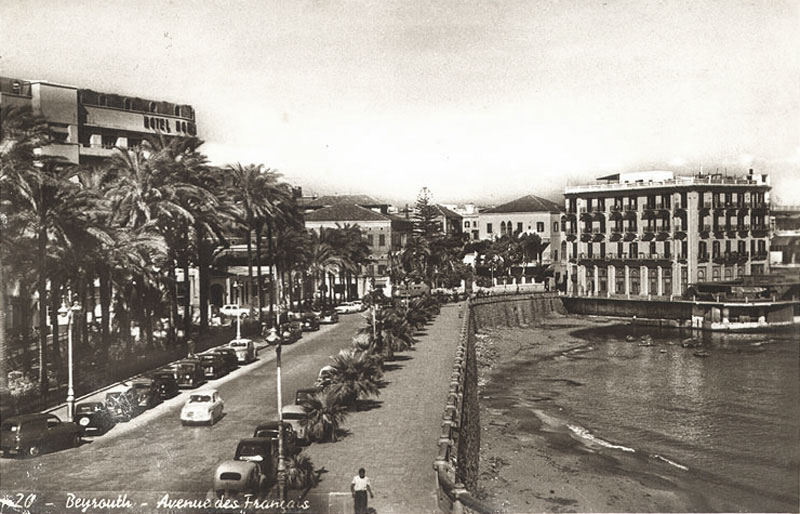

Beirut is a remarkable city with a layered history dating back at least 5,000 years. It was destroyed and rebuilt by the Greeks; conquered by the Romans, the Muslims, the Ottomans; and then ruled by the French, before gaining independence only to tear itself apart in a sectarian civil war from 1975 to 1990. Today, less than thirty years after the conflict which destroyed swathes of the Lebanese capital, Beirut’s reconstructed downtown glows from the warmth of its rebuilt limestone buildings.

In a city bordered by the Mediterranean, the disconnect between the sea’s holiday-brochure beauty and its current status as a site of migration and death is impossible to avoid. But Beirut has a reputation as a city which has sheltered displaced people for centuries. 100 years ago, Armenians fleeing genocide in Turkey came by boat; waves of Palestinian refugees arrived following the 1948 Arab-Israeli war; more recently, displaced Syrians have migrated to Lebanon in such high numbers that the country’s famous tolerance towards those seeking refuge is under increasing strain. Today, an estimated one-third of Greater Beirut’s approximately 2 million population is comprised of migrants and refugees.

And yet, in other ways, Beirut is remarkable for all the wrong reasons. Public transportation is effectively non-existent—the wealthy drive or take taxis, the poor use an informal bus network. Electricity is subject to daily three-hour outages, with more severe shortages across Lebanon. These gaps are eagerly filled by private companies (many, I’m told, with connections to politicians) via generators at inflated rates. Over pumping from Beirut’s water wells has contributed to the infiltration of seawater into aquifers and many buildings rely on private water tankers or costly desalination equipment. And so, although on the surface, much of the city appears restored, the breakdown of public infrastructure means that in many respects this rebuilt city is a veneer.

I’m in Beirut for the seventh Beirut Design Week, founded in 2012 by designer Doreen Toutikian. This year’s theme is ‘design and the city’ and many participants reflect on the gaps in government services and the designer’s role in either filling those gaps or prompting citizens to take the initiative. Newly-installed creative director Ghassan Salameh reflects on the theme’s significance. ‘I think today this is the most relevant topic for discussion in any city across the world,’ he says. ‘We have to ask ourselves hard questions—not just as designers, but as people—because so many things have gone wrong, from the rise of the far right to inequality and housing, about how we can make our cities better places and better spaces.’

Time spent in Beirut brings to mind an article written by former Icon editor turned Design Museum curator, Justin McGuirk, for uncube in 2014. There, he argues the dangers in conceptualising DIY- and user-generated cities as representatives of the embodiment of progress, rather than alarming signifiers of long-term government neglect. ‘It is a truism that while people can build themselves homes and entire communities,’ he writes, ‘they cannot build themselves a transport network. For that, traditionally at least, one needs government. The complexity and cost of urban infrastructure have thus far defined the outer limits of self-organisation.’

I test out McGuirk’s reasoning on a number of designers and activists I meet in Beirut and they instantly and vehemently bat it away. ‘That sounds like an argument made by someone who has never had to live in a city like ours,’ says Mona El-Hallak, an architect and tireless activist for Beirut’s historic built heritage.‘Frankly, the political corruption here, I’m sorry to say, is beyond redemption and we have no choice left but to do it ourselves.’

And so, alongside new product exhibitions and designers’ open studios, a major focus of this year’s Beirut Design Week explores DIY infrastructure and participative, networked urbanism. Of the two most striking projects, one is an exhibition by Public Works Studio presenting a number of research projects connected by mapping. The other sees an entire street in the Ras Beirut neighbourhood remodelled with a series of interventions created by different designers.

Despite rapid development, Ras Beirut, a prosperous neighbourhood which includes the American University of Beirut, has managed to retain some of its historic buildings and chaotic charm. Stemming in part from the University’s desire to engage more meaningfully with its surroundings, the Jeanne d’Arc street initiative was designed both to improve the public realm, by providing a model for other streets throughout the city, as well as to generate and catalyse civic engagement within the neighbourhood.

Earlier in the week, during a BDW panel discussion on design and governance, an audience member raised the issue that Beirutis lack social norms for sharing and maintaining public space. Given the absence of governmental oversight, he said, residents care only for their private spaces while allowing public spaces to rot. In many respects, the interventions dotted along Jeanne d’Arc Street are an attempt by Beirut’s designers to answer the question of how to establish shared social norms in public space, as well as to demonstrate ways in which individuals can improve the public realm in the face of governmental indifference.

First proposed in 2015 by the AUB Neighbourhood Initiative and carried out in collaboration with the Beirut Municipality, the key intervention is significant, if invisible to the uninformed eye. In a city where cars park anywhere irrespective of regulations, an entire parking lane on the west side of Jeanne d’Arc street has been ripped up. The pavement has been widened and secured for pedestrians by a series of benches and bollards. ‘This is now the only place in the city where you can walk for 30 metres without having to look down at your feet,’ El-Hallak says.

Halfway down the street, District D’s bright Red Reading Hood stands out against the fat black column it is secured to. Red Reading Hood combines a covered seat with two bookshelves, already partially-filled by locals. The designers, a multi-disciplinary collective, acknowledge that while their community-maintained public bookshelf may seem unremarkable to a Westerner, it’s something completely new to Beirut which they hope will engender a new way of thinking about public space.

Similarly, Adrian Muller’s sleek Urban Cigarette Waste Receptacle seeks to change smoking norms. Although smoking indoors has been illegal in Lebanon since 2012, the behaviour persists as the law is not enforced. On Jeanne d’Arc Street, Muller’s receptacles have been attached to three light posts and El-Hallak says that the receptacle is as much about changing behaviour as it is cleaning litter. ‘We placed one outside the pub and encouraged people to deposit their butts,’ she says. ‘And gradually, people have started smoking outside next to the receptacle rather than in the pub. So, you can change social norms, but it takes time.’

Across town in Beit Beirut—formerly the 1924 Barakat house, built as middle-class apartments; later a civil war sniper base, and recently restored by Youssef Aftimus following a preservation campaign led by El-Hallak—Public Works Studio’ Mind the Map exhibition looks at similar civic engagement and infrastructure problems on a broader scale through the lens of mapping. ‘All of these projects look to mapping as a tool for understanding and changing the city,’ says exhibition curator, Monica Basbous. ‘But it’s important to note that mapping does not necessarily equate to cartography, as mapping can include human geographies or stories where cartography only represents spatial information.’

The exhibition includes a fascinating display by theOtherDada, Beirut River 2.0, outlining the history of Beirut’s river from the Roman era to the present day. Twentieth-century developments, such as the construction of river walls in the 1950s and 60s, have contributed to current problems with river water pollution, sewage runoff and degraded biodiversity. Ultimately, the project aims to bring life back to the river and improve living conditions for adjacent communities by testing and evaluating different strategies on small sections before broader application.

Another inspiring project, Greening Bourj Al Shamali Refuge Camp, works to improve living conditions in Bourj Al Shamali, a predominantly Palestinian refugee camp in south Lebanon, through the creation of green spaces. As a first step, the project worked with a local youth citizen science group to map the camp using a low-cost balloon-based aerial camera. If this map creation seems unnecessary, Basbous insists that a community-created map is an empowering tool. ‘It’s an incredible project in part because it developed a low-cost way of directly mapping territory,’ she says. ‘We don’t have a centralised office where it’s easy to obtain territorial maps. So, every time you start a new project and you need a map, you have to request one from people like the military. And of course, you have to pay.’

It’s difficult to spend time in Beirut without feeling awed at the way the city has rebuilt itself after the civil war, dismayed how that rebuilding has in turn destroyed parts of the city’s history and heritage, and enraged on behalf of the people who live every day with crumbling infrastructure and political corruption. One night at dinner, during a frank conversation with a successful Lebanese art director, I admitted that I didn’t think I could live in Beirut, given the overwhelming sense of daily struggle. I wondered how people coped, let alone thrived. ‘For all its messiness, chaos, even corruption,’ she said, ‘we stay and fight because here we feel free. Completely free.’

Originally published in Icon, September 2018