I’ve started working on my final year MFA project – a series of works in different media looking at the history of the concepts of uncertainty, progress and crisis – across physics, epistemology, political theory and literature – and how this history informs present understandings of the three concepts.

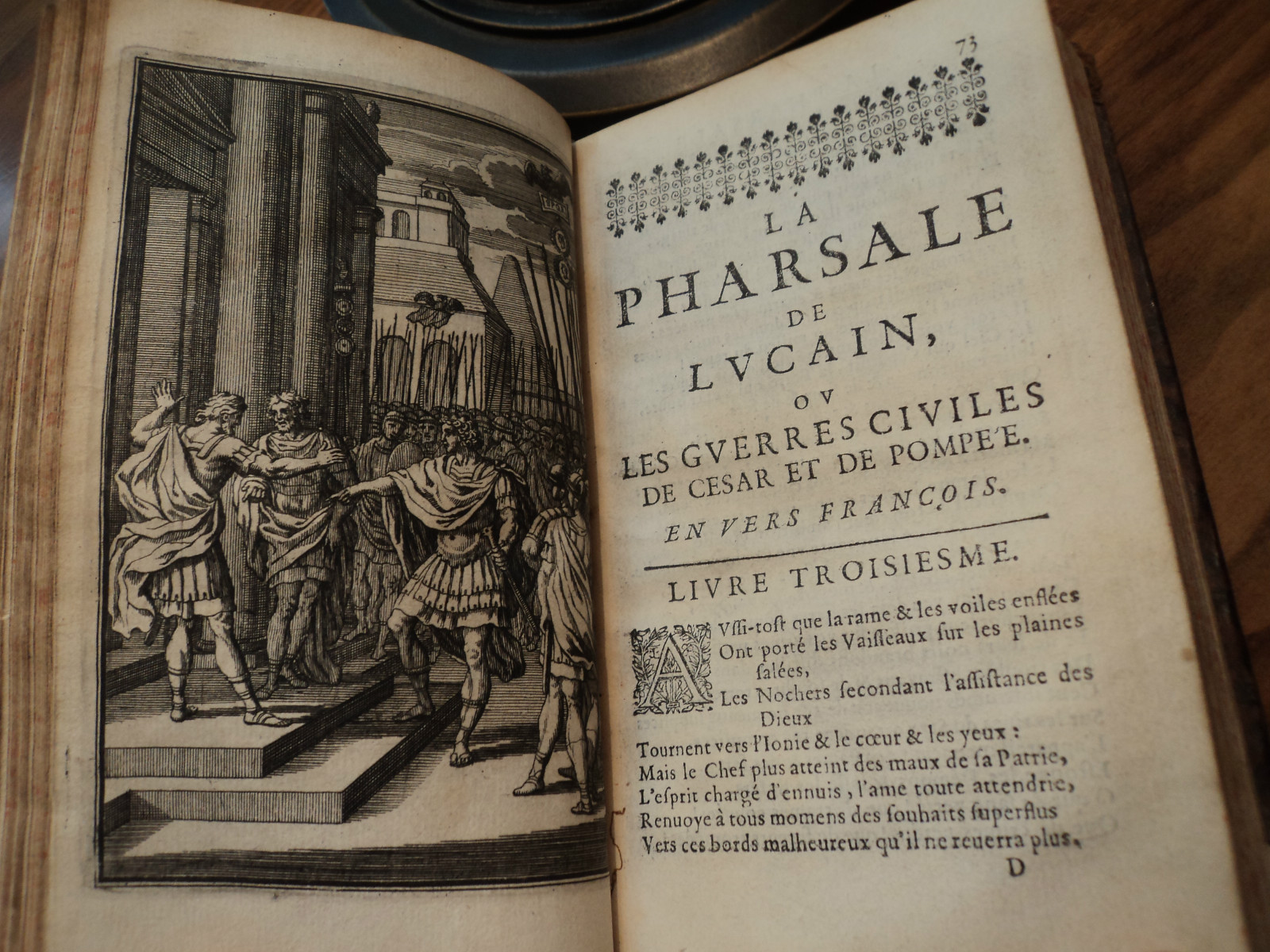

I’ve been thinking of a way to bring Lucan’s Pharsalia, which was the text I studied for my DPhil., into the fold of this project partly because I love it, but also because I think it works well as a starting point for a loose conceptual history of “crisis”.

There’s something about contemporary rhetoric, particularly in a news context, in relation to the use of the word crisis which I find deeply unsettling and extremely ahistorical. Housing crisis, oil crisis, environmental crisis, terror crisis, suicide pilot crash crisis, Eurozone crisis. The word becomes almost meaningless in its constant overuse. My reading of the present moment as one beholden to the idea of crisis stems from what seems to be an underlying cultural anxiety about information overload (coupled, perhaps, with a lack of “real” knowledge), the media’s need to make profit by the selling of constant catastrophe, decision-making fatigue, and the digital present’s lack of a filter. All of these factors, plus others no doubt, aid us in our collective efforts to privilege the present as an urgent time of crisis, viewing the past as a far more benign period of crisis-free living. They never had to deal with housing shortages, global warming or airplane hijackings. Never mind that the render ghosts of the past had to deal with famine, enclosure, plague, war, nuclear bombs, etc.

One of the reasons I love the Pharsalia in the context of undercutting assumptions about contemporary notions of crisis is because, not only does it take as its subject an important historical moment of crisis (nearly 20 years of civil wars) – when Rome lost its so-called freedom – but because it also takes a no-mercy approach to apportioning blame. In his inimitably vitriolic style, Lucan chastises the major actors – Pompey, Caesar and Cato – for their part in the crisis, but he reserves his harshest judgement for the Roman people, who he holds primarily responsible for the loss of the freedom of Rome.

The following passage describes the scene as Caesar enters Rome with his troops, after crossing the Rubicon.

Sic fatur, et urbem

Adtonitam terrore subit. Namque ignibus atris

Creditur, ut captae, rapturus moenia Romae,

Sparsurusque deos. Fuit haec mensura timoris:

Velle putant, quaecumque potest. Non omina festa,

Non fictas laeto voces simulare tumultu:

Vix odisse vacat Phoebea palatia complet

Turba Patrum, nullo cogendi iure senatus,

E latebris educta suis. Non consule sacrae

Fulserunt sedes: non proxima lege potestas

Praetor adest: vacuaeque loco cessere curules,

Omnia Caesar erat. Privatae curia vocis

Testis adest. Sedere Patres censere parati,

Si regnum, si templa sibi, iugulumque senatus,

Exsiliumque petat. Melius, quod plura iubere

Erubuit, quam Roma pati.

Pharsalia, Book 3: 97-112

So he descends to a city thunderstruck by terror.

For they believe he will torch the walls of Rome,

scotch it like a captured city, scattering her gods.

This was the extent of their dread: they think his will

is equal to his power. No one has time to invent

good omens, or to feign a shout of acclamation,

let alone dissent. A mob of patricians

packs the Palatine temple of Phoebus, and a Senate –

convened without authority – is brought out of hiding.

No sacred benches shine with consul’s cluster,

and the praetors, next in lawful power, are absent,

their empty ivory chairs are moved from their places.

Everything was Caesar. The Senate assembles as witness

to one man’s private interests. The fathers were prepared

to sit and vote, should he seek monarchy, or a temple,

or even the throats and exile of the Senate. Good thing

he blushed as demanding more than Rome would endure.

From Matthew Fox’s 2012 Penguin Classics translation.