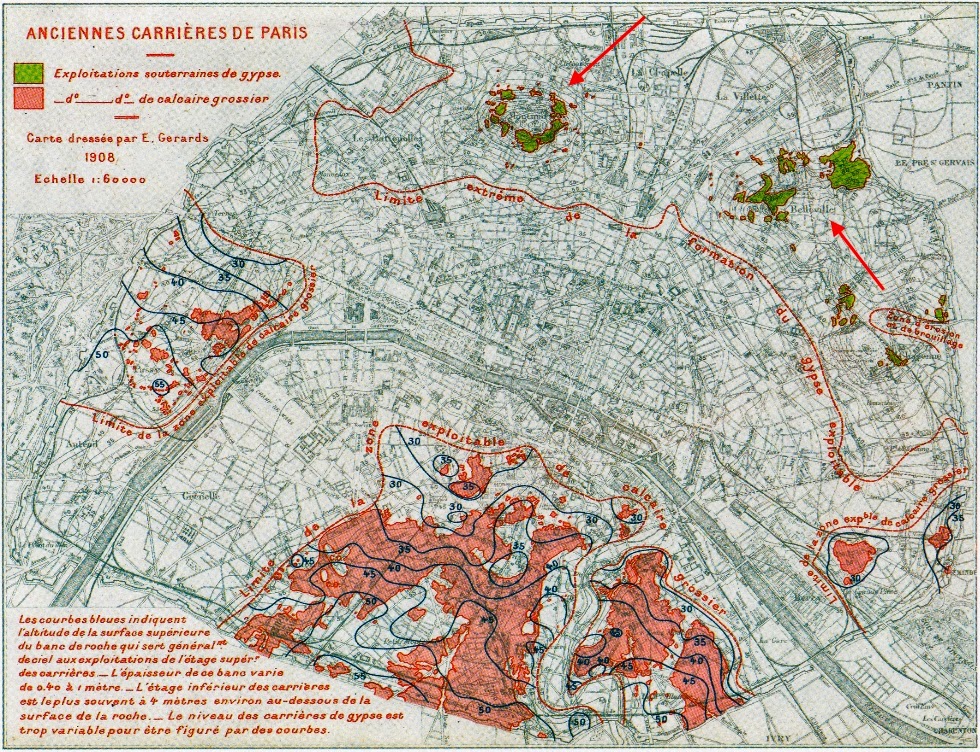

I’ve recently started working on a new project about the quarries underneath Paris, limestone and urban geology. Since it’s still very early in the process, everything is a bit of a jumble in my mind – I know I want to look at the relationship between the history, labour, materials and processes which contributed to the building of the city and the ways in which, historically and physically these things have become invisible, despite the fact that much of the infrastructure is just below the surface of the city.

I’ve been digging in the archives and reading everything I can find (which, incidentally, is a lot. Ahh, the French and their love of archives), but there’s nothing quite the same as first-hand knowledge. Before we moved to Paris, I contacted Gilles Thomas, who is one of the leading authorities on underground Paris. Although the office which was established under Louis XVI in 1777 – L’Inspection Générale des Carrières – has done much good by way of mapping networks and systems and reinforcing the former quarries to prevent sinkholes and building collapses, they are less interested preserving and promoting the history of the city’s underground. Gilles, on the other hand, is incredibly passionate about documenting and preserving these important spaces, without which, Paris would not be as it is today.

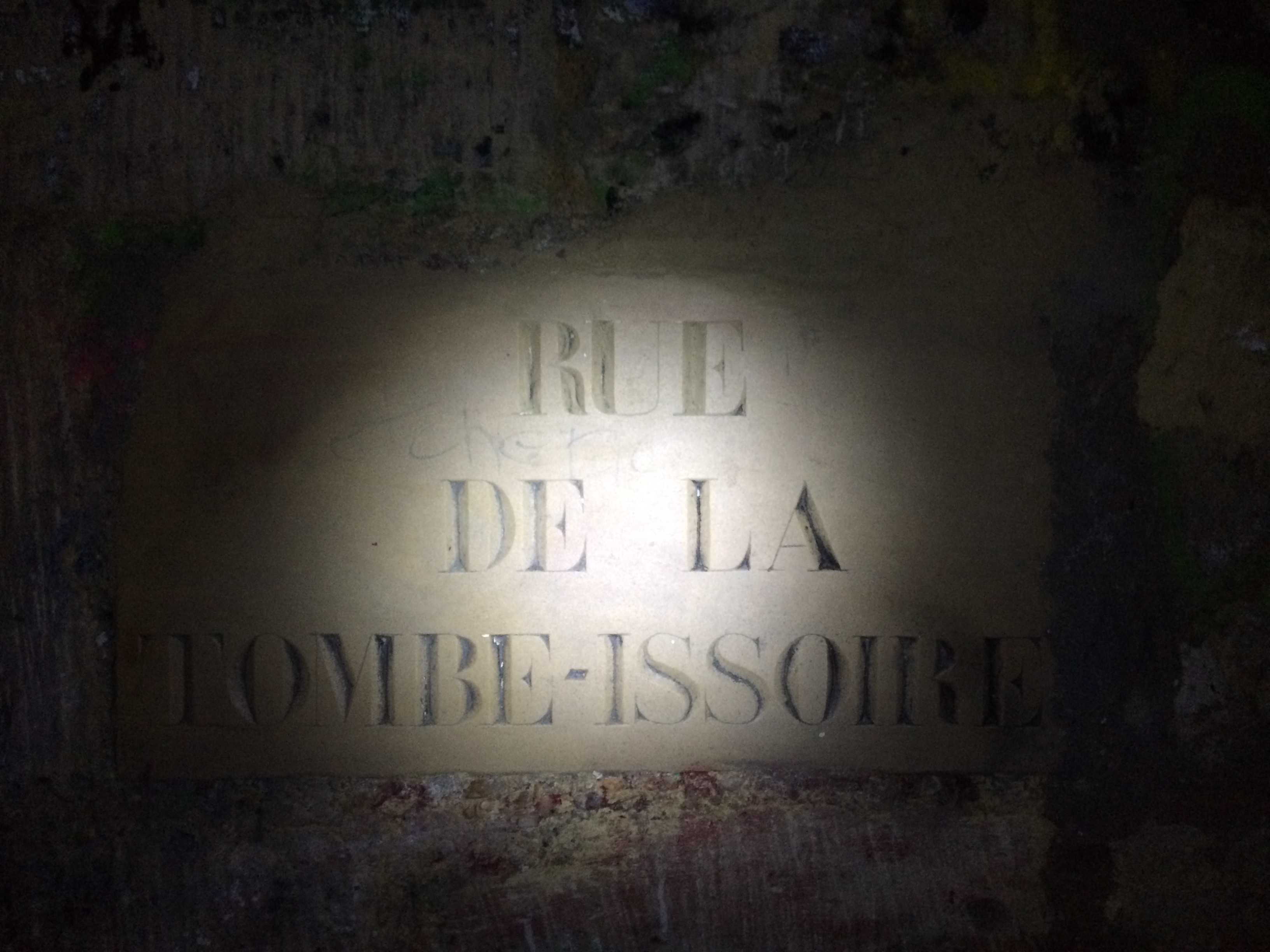

The following are photos from my first visit to the Grand Réseau Sud, a large network of 100km of tunnels under the 5th, 6th, 14th and 15th arrondissements of Paris. Prior to the 19th century, the GRS was in fact a series of fragmented quarries, dating from the 13th century onwards. By the 17th century, the city’s expansion began to occupy land formerly used for quarrying – a number of large construction projects in the late-1600s spent a great deal of money reinforcing caverns left by abandoned mining enterprises. 100 years later, the growing city continued to expand at an ever faster rate. The disaster which in part precipitated the founding of the IGC occurred in one of these far-flung expansions – in 1774, some 30 metres of street collapsed to a depth of 30 metres.

For this first trip, we visited the Quartier Sarrette, which is apparently one of the most visited areas of the GRS. Cataphiles is the name for people who visit the regularly quarries, but for people who supposedly love something, it was incredibly depressing to see evidence of pretty poor treatment. Graffiti covers practically every surface and there’s trash everywhere – I don’t have a problem with graffiti per se, but it’s so frustrating, when you’re trying to understand the history of a place, not to be able to see it properly. Gilles said that back in the ’80s, when he first started visiting the quarries, there was no graffiti at all. I wish I could have seen it like that, but then again, it’s pretty amazing to be able to see it at all, considering how many people will never be able to.

More trips soon.